A THREE-CAR convoy is considered modest for leading Nigerian politicians, and modesty appeals to Muhammadu Buhari, the leading opposition candidate in the presidential election due to be held on February 14th. From his rented house made of simple concrete with few windows, his cars drive into a busy street and are almost immediately stuck in traffic. Without the armed outriders and flashing lights that ease the passage of officials in the ruling party he inches his way to the airport in Abuja, the capital, his aides glancing around nervously.

The aura of power catches up at the terminal building as he prepares to start the day’s campaigning. Courtiers, jobseekers and hangers-on in colourful garb and headgear rush in. Shyly he shakes hands. Mr Buhari, a 72-year-old retired general who ruled Nigeria for 20 months in the mid-1980s (and then spent 40 months in detention), may be on the verge of triggering the first democratic change of power in the country’s modern history. Polling and observers suggest the race between him and the incumbent, Goodluck Jonathan (pictured) is too close to call, with each commanding about 42% of the vote (see chart).

Ever since 1999, when the army relinquished power, Nigeria has been ruled by the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), a sophisticated political machine greased by billions of dollars’ worth of oil money. Yet less cash is available these days. A sharp decline in the oil price has coincided, unluckily for Mr Jonathan, with the election. Government revenues have halved in recent months and the currency has tumbled by a quarter. Civil servants are paid late, if at all. Infrastructure projects have stalled.

But the government’s biggest liabilities are the result of its own greed. Officials have never been shy about dipping into public troughs but the present lot is, by common consent, especially avaricious. Last year the governor of the central bank said that $20 billion had gone missing. He was sacked for his trouble. A report into his allegations is now on Mr Jonathan’s desk. Rampant theft has not only harmed the economy and exacerbated poverty but it has also contributed to public insecurity.

With corruption endemic even in the army, soldiers are sent to the front line short of ammunition and rations. Demoralised and poorly led, they have failed to quell a jihadist insurgency in the north-east that has killed thousands. Almost a year ago militants from Boko Haram, a jihadist group that claims to have established a “caliphate” over a chunk of the country, kidnapped more than 250 girls from the town of Chibok. The government barely stirred until it was goaded into action by an international outcry.

With much of the north-east in flames—around 1.5m people have been forced to flee their homes—many voters believe Nigeria’s situation today is worse than at any time since the civil war in the late 1960s. To be sure, large parts of the country remain secure and the economy has boomed in recent years, but insecurity is spilling southward. Left unchecked, the insurgency could tear Nigeria apart.

At rallies, Mr Jonathan encounters unenthusiastic supporters; many are paid to turn up and so leave before his speech ends. Chairs are provided, perhaps to make the crowd seem larger. At a rally in Yola in late January they were thrown at him. Elsewhere his convoy has been stoned. Some election billboards are guarded by soldiers, giving rise to calls that the men should fight Boko Haram instead.

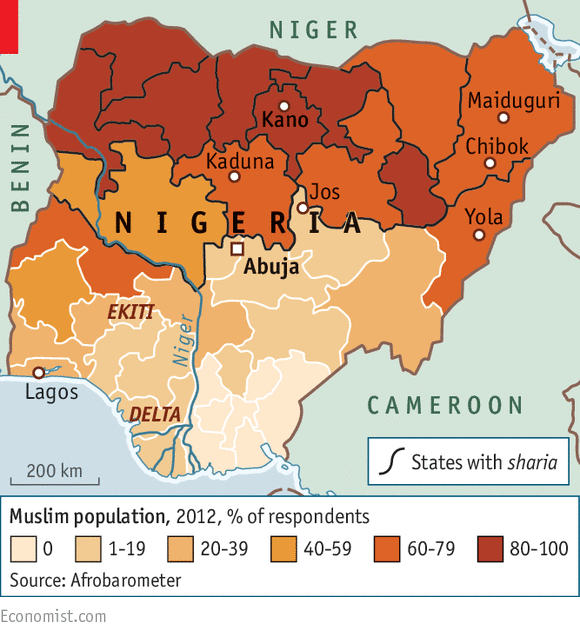

The candidates, and their parties, exhibit few ideological differences. The election revolves around questions of honesty and competence as well as ethnic and religious identity—unsurprisingly, given Nigeria’s diversity, with 500 languages spoken among its almost 200m people. Mr Jonathan is a Christian from the south whereas Mr Buhari is a northern Muslim (see map).

The key to victory for either candidate may lie partly in whether people vote along religious lines. To win, Mr Buhari must convince Christian voters, predominantly in the south, that being Muslim is not synonymous with Islamism. The atmosphere at Buhari rallies—even those held away from his northern heartland—suggest that momentum is on his side. Many attendees are euphoric with optimism that he can fix the country.

They also hope that, as a former military man, he knows “how to make soldiers fight, not run away.” He has some form. Under his command in the early 1980s the Nigerian army drove out Chadian rebels from areas now held by Boko Haram (and which, ironically, are now being contested by Chadian soldiers who have been sent to assist Nigeria).

They also look at his record in fighting corruption. When he was head of state he, rather unusually for the office, kept his fingers out of the till. He locked up hundreds during an anti-corruption campaign and launched a “war against indiscipline” in which he got whip-wielding soldiers to enforce orderly queuing. Civil servants who arrived at work late were forced to perform “frog jump” squats.

Yet, during this period thousands of political opponents were detained without trial, political meetings were banned and the press was tightly controlled. Hundreds of people were tried before secret military tribunals and many were executed for crimes that were not capital offences when they were committed. Eager to play up his past the PDP has been publishing photos of him in military uniform with the headline, “Once a dictator, always a dictator”.

Activists and foreign diplomats are unworried by his past. His running mate, Yemi Osinbajo, is a lawyer and pastor with a strong record of championing human rights. Mr Buhari, for his part, told The Economist: “We have to stick to the constitution of the country. Once upon a time I was a military man. But I do not want to militarise democracy.”

If anything, Mr Buhari’s biggest flaw is the opposite of what the PDP alleges. He has never been a forceful character; he can be Reaganesque in his inclination to set the tone and direction of policy but leave the details to others. His party, the All Progressives Congress (APC), is the product of a recent merger of the four main opposition groups. Ruling-party bigwigs dismiss it as a “party of candidates” squabbling for power. Attempts to form a united opposition party at previous elections failed because the leaders could not agree on a joint candidate. This time they did, holding a credible primary before choosing Mr Buhari.

The APC has, moreover, already shown it can govern competently. It runs the two most populous urban areas, Kano and Lagos, and almost half the federal states. Supporters on both sides have threatened to protest violently against a loss. Tempers will probably also flare if there are widespread irregularities in the conduct of the vote (see article). Some fear a Buhari victory could lead to an eruption of violence in the Niger Delta, the home region of Mr Jonathan, where the government has bought a precarious peace by paying off former militants. A victory for Mr Jonathan could, meanwhile, spark unrest in the north. The vote in 2011 was judged one of the country’s fairest, and yet almost a thousand people died in communal fighting.

This election could mark a permanent shift in Nigerian politics away from one-party rule. The powerful used to crowd around one big trough, awaiting their turn. Now they must choose between two troughs. That makes for potentially nastier politics. But if Nigeria can hold together, there is a hope of better government.

No comments:

Post a Comment